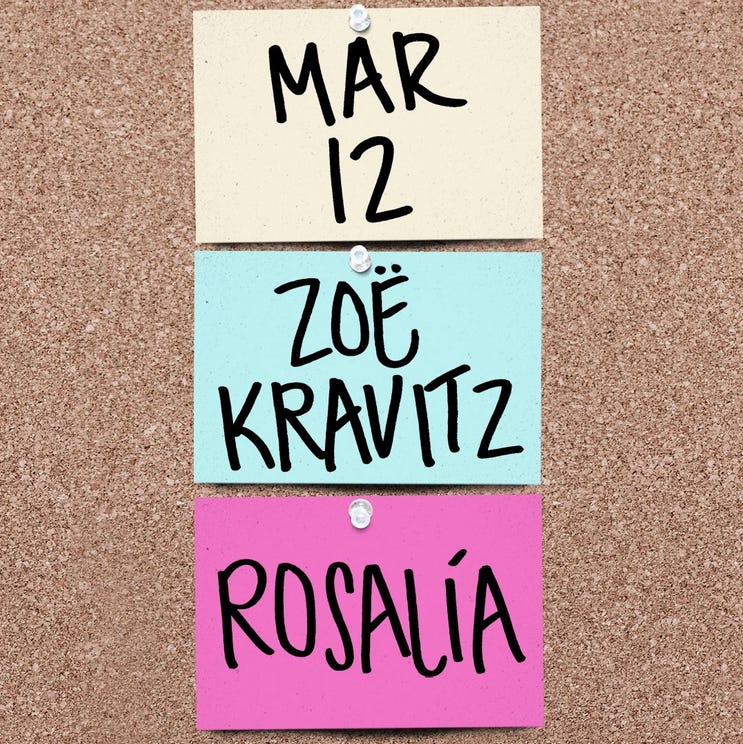

Zoe Kravitz on SNL: the Hilarious Amazon Sketch

Digital economies don't work for everyone (aka buying bread in the age of surveillance capitalism).

(photo credit: NBC)

Last month Zoe Kravitz hosted Saturday Night Live (SNL), in part to promote the movie Batman in which she plays Catwoman. She was incredibly funny and the whole thing is worth watching.

But what I really loved was the sketch she did about Amazon Go supermarkets and shopping in them while black.

To shop in Amazon Go supermarkets, you download an app, then the digital technology instore knows what you’ve purchased and the final amount is charged to your Amazon account, so you can walk out without using money to pay.

In the sketch, written by Tucker/Jackson (see below), Kravitz and the other black cast members walked around the Amazon-style makeshift set acting bewildered and confused. The sketch showed off their disbelief that it could be that easy to walk out. Some tried to leave money at the entrance, while others asked their white partners to pick the produce off the shelves instead.

I laughed with a sense of familiarity while watching this, because being black, I know that doing anything - going to the bank, walking in the park or going for a jog- while having black skin can be problematic. There’s a 50% chance of going about our day without being bothered, and a 50% chance that just by doing these daily activities we’ll be in danger somehow. There is no promise of ease of movement or guaranteed safety.

SURVEILLANCE CAPITALISM

The best thing about the sketch though was that it offered up a humorous way to analyse a rising societal problem: Surveillance Capitalism. The brilliant Harvard academic Shoshana Zuboff has a book called The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: A Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, which explores this very modern phenomenon.

Zuboff’s book is part political and part economic. In it she tracks how, over time, tech companies have increased their power to use our data to serve their primary aim: to make money. Most of the stuff Zuboff writes about in her book we, as consumers, already know. We buy these tech products, we don’t read the lengthy terms and conditions, and then we feel outraged when some of these companies reveal the ways in which they inadvertently became part of our most intimate moments.

It’s like that scene in the TV show Billions, season 6, episode 1:

“We can’t have invaded your privacy, you invited us in. Each of you gave permission when you launched the app and clicked agree.”

“Everyone always just clicks agree, you tricked us.”

There is a sense of helplessness and hopelessness with it all, it seems too hard to fight the swell of progress and innovation in this new digital future. It’s not like we can go back to Nokia phones without voice recognition software embedded in them or use fax machines that can’t be tampered with. We have progressed too much to turn back.

But that doesn’t mean that we can’t have rich and deep conversations about what’s going on. And that’s where the SNL sketch and the brilliant 2020 Netflix documentary called The Social Dilemma come in. These pop culture TV moments cause us, as a society, to start talking. To start thinking about if we are comfortable with a future where our purchasing power is intrinsically linked to our person. Where AI sensors, or audio and facial recognition software are the gold standard, even though we know that those building the digital infrastructure don’t reflect the diversity of wider society but are in charge of handling and processing our personal, sensitive data.

To be clear, Amazon states on its website that it doesn’t use facial recognition in its stores, but sensor technology instead: "Our checkout-free shopping experience is made possible by the same types of technologies used in self-driving cars: computer vision, sensor fusion, and deep learning."

THE PRICE OF VISIBILITY FOR POC, WOMEN AND THOSE LIVING IN POVERTY

At start of the 1990s, similar discussions were being held about the rise of the Internet, who can access it, how we police it and who designs the platforms that live on the web. Having seen how those discussions went down- the result being an internet that was carved up into big chunks, where access is granted via a handful of Big Tech providers– we have the chance to learn from that mistake.

As we build this new digital economic landscape, a landscape where the personal and the digital meet, there’s a fresh opportunity to implement fairer systems with less bias. This is particularly important for women, people of colour and those in poverty.

In his book, The Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison, the famed black writer, says “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me…I am not complaining, nor am I protesting either. It is sometimes advantageous to be unseen, although it is most often rather wearing on the nerves.”

This sentiment acknowledges the double-edged sword of fighting to be seen when you are not white, male or straight. On the one hand, visibility feels so important for those of us from marginalised communities. We know that the generations who came before us fought for their right to be seen, to have their humanity recognised- a fight that continues today with the reparations sought from the Tulsa Race Massacre, and in the UK with the recent Windrush scandal.

In the TV show Lovecraft Country, the words of Afrofuturist Sun-Ra are played over a scene featuring a black female character trying to articulate how she wants to be seen as she moves through the world.

The whole of episode seven, aptly titled ‘I AM’, grapples with this idea of identity. Taken from the Sun-Ra film "Space is the Place”, made in the 1970s to reflect life in the 1950s, we hear the words:

“I’m not real, I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. If you did your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. You’re not real, if you were you’d have some status among the nations of the world. So, we are both myths.”

We have fought so very hard for the right to be, have endured so much to be able to stand here today, we must be careful not to shrink.

And yet, maybe there is also power in being invisible. In not trading the data on our faces in order to see what a new lipstick will look like or to buy a loaf of bread. Journalist Arabelle Sicardi explored this idea in a brilliant article she wrote for the now defunct website Lenny Letter. Back in 2018, Sicardi interviewed expert Simone Browne, author of Dark Matters, a book about “how contemporary surveillance technologies and practices are informed by the long history of racial formation”. In the article Browne commented on what it feels like to occupy these spaces when you are ‘other’: “Could there be some potential in going about unknown or unremarkable, and perhaps unbothered, where CCTV, camera enabled devices, facial recognition, and other computer technologies are in use?”

HOW CASHLESS SHOPPING BECAME THE FUTURE OF RETAIL

While we’re accustomed to trading our credit card data and email addresses for online purchases, we do so knowing that we also have the freedom to run down to the local supermarket with some change in our pocket to purchase this way as well. But now, it seems that digital-heavy transactional relationships are transforming brick and mortar retail. This innovation in retail tech is so far being promoted as being better for the consumer (it’s easier, quicker, no more standing in line!), but only some consumers really benefit.

Downloading an app to get your food shopping only works if you can afford a smartphone and the data to keep it running. If not, you are automatically edged out of participating in this basic economic activity. With the rise of cashless supermarket shopping, we’re creating a divide in terms of equality and access, which is only going to get worse as the global cost of living crisis builds.

In the UK, campaigns to support those who depend on the cash economy, rather than the digital one, is picking up speed. There’s been some brilliant reporting by Which? The consumer title is campaigning for the protection of cash for everyone, but particularly for those with a range of needs who depend on cash to exist and access services.

Natalie Ceeney CBE, also headed up the ground-breaking Access to Cash Review, which examined “future trends in cash usage”, rapid bank branch closures, and the speed at which the cashless/digital-first economy is accelerating. Walking headfirst into a cashless society might not be a problem if you have a digital bank card and a high street bank account, plus you live in a city where you have a choice of bank branches and your house has great wifi, but you definitely feel the impact if you live in a rural area, with poor connectivity. While the cashless society works for the majority, particularly those in higher income brackets, but that doesn’t make it fair.

Before the pandemic, the issue of cashless retail was already being discussed by lawmakers. Back in February 2019, Philadelphia passed a bill preventing stores from going cashless to keep shopping in the city accessible for all.

(image credit: https://unsplash.com/@sarahagnewcouk)

But post pandemic, businesses now mandate how consumers pay. The Guardian reported that at the start of the pandemic, UK supermarkets were refusing to accept cash, leaving the most vulnerable unable to get basic goods, from bread to nappies.

And we’re seeing supermarket retail in the UK follow the Amazon example with a move towards cashless stores, run on high-level tech capabilities, which track everything from what you bought to guesstimating if you are old enough to grab that bottle of wine.

Aldi just launched a cashless supermarket called the Aldi Shop&Go concept store, based in Greenwich. According to the company press release, the in-store tech comes from “leading technology provider AiFi,” and “uses specially positioned cameras to detect which products customers have picked up, before charging them to their Aldi Shop&Go account when they leave the store”. There’s also the option to have a member of staff help with age verification of products, rather than the tech. “Customers wishing to purchase alcohol, or other Challenge 25 products, will be able to use facial age estimation technology to authorise their purchase. This technology, provided by Yoti, enables customers to confirm their age within seconds via the Aldi Shop&Go app. Those who opt to not use the system will instead be age verified by a store colleague”- Aldi Press Release.

Tesco also opened a similar checkout-free store in October 2021, called GetGo, where customers can “shop and pay without scanning a product or using a checkout”. According to its website, Tesco says that “cameras and weight-sensors” are used to understand what customers have bought and then on the way-out those items are charged to their app. It also revealed that the in-store “cameras do not use facial recognition technology, but instead track body movements. Visual data from customers will not be stored or saved.”

RETAIL’S NEW WORKFORCE

The role of AI in retail is only going to increase, especially as the industry looks to become more efficient. Supermarket retail in the UK is already moving from fully self-service till areas, with mini CCTV cameras attached to them, to standalone cashless stores, with a sprinkling of staff to make sure that the tech behaves itself.

“We are moving from a globalised world of manufacturing giants to a networked one of technology giants…Left to itself, this sort of economy is also a recipe for massive inequality and insecurity.” -Tim Dunlop, The Guardian.

Making sure that this new world is equitable matters. That means hiring a diverse pool of STEM graduates to design these digital systems. It also means supporting a job market impacted by the pursuit of streamlined efficiency and reduced staffing costs. This isn’t just about equality, it’s about economics.

And while supermarkets are not using controversial facial recognition tech, in bigger shopping malls, the use of facial recognition has been reported.

Dean Armstrong, a UK based human rights lawyer who spoke to the BBC for its show File on 4: Facial Recognition revealed how this technology had been used within retail settings to prevent crime, but not every instance of usage had been acceptable. “You can deploy measures to stop crime, but they may be disproportionate…we are here talking about use of data, which is, by its very nature, extremely sensitive.”

The reporter from the BBC show, Geoff White, revealed the case of the Trafford Centre, where in 2018 it was reported by Manchester Evening News that surveillance was used without the consent of shoppers.

“An estimated 15 MILLION people” [were] potentially caught in a surveillance pilot set up by Greater Manchester Police, “the programme was designed to match faces to a 'watchlist' of wanted criminals and around 30 missing people. Just one suspect was caught between April and September - a man wanted on recall to prison. The secret pilot was dramatically halted… after the Camera Surveillance Commissioner Tony Porter raised concerns.”

In response to outrage about the usage, Intu Properties, the owners of the Trafford Centre at the time, released a statement saying: “We take data privacy very seriously and would like to reassure our customers that no images of the general public were retained through the use of AFR."

This brings up the issue of what happens to the digital imprint of your face after a quick trip to the shops, does it stay on a watch list or is it erased after six months? Shopping in this new digital-first retail economy, means understanding that the UK has an Information Commissioner called Elizabeth Denham who can use UK law to enforce the protection of our data but also understanding that the relationship between tech, retail and data is evolving in real time, which means that the law is often left playing catch up. This MIT article about facial recognition algorithms What Happens When An Algorithm Gets It Wrong, reveals how current tech still misgenders people and even gets their race wrong.

Yes, innovation is exciting and unstoppable, but it also results in society having to fix the problems in real time, as they reveal themselves. Something to keep in mind when you go shopping for your Easter eggs later this month.